Managers Can’t Be Great Coaches All by Themselves

In a utopian corporate world, managers lavish a constant stream

of feedback on their direct reports. This is necessary, the thinking goes,

because organizations and responsibilities are changing rapidly, requiring

employees to constantly upgrade their skills. Indeed, the desire for frequent

discussions about development is one reason many companies are moving away from

annual performance reviews: A yearly conversation isn’t enough.

In the real world,

though, constant coaching is rare. Managers face too many demands and too much

time pressure, and working with subordinates to develop skills tends to slip to

the bottom of the to-do list. One survey of HR leaders found that they expect

managers to spend 36% of their time developing subordinates, but a survey of

managers showed that the actual amount averages just 9%—and even that may sound

unrealistically high to many direct reports.

It turns out that 9% shouldn’t be alarming, however,

because when it comes to coaching, more isn’t necessarily better.

To understand how managers can do a better job of

providing the coaching and development up-and-coming talent needs, researchers

at Gartner surveyed 7,300 employees and managers across a variety of

industries; they followed up by interviewing more than 100 HR executives and

surveying another 225. Their focus: What are the best managers doing to develop

employees in today’s busy work environment?

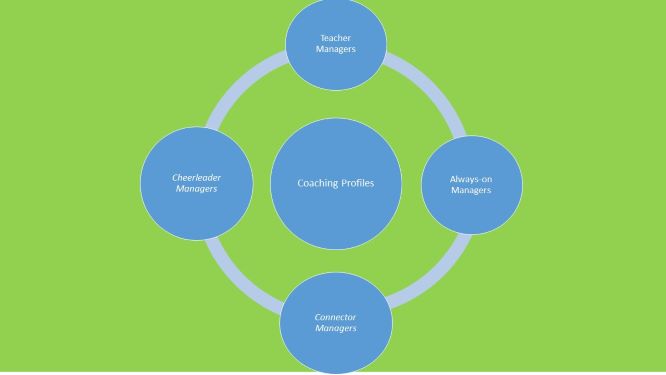

After coding 90 variables, the researchers

identified four distinct coaching profiles:

Teacher Managers coach employees on the basis of their own knowledge and experience, providing

advice-oriented feedback and personally directing development. Many have

expertise in technical fields and spent years as individual contributors before

working their way into managerial roles.

Always-on Managers provide continual coaching, stay on top of employees’ development, and give

feedback across a range of skills. Their behaviors closely align with what HR

professionals typically idealize. These managers may appear to be the most

dedicated of the four types to upgrading their employees’ skills—they treat it

as a daily part of their job.

Connector Managers give targeted feedback in their areas of expertise; otherwise, they connect

employees with others on the team or elsewhere in the organization who are

better suited to the task. They spend more time than the other three types

assessing the skills, needs, and interests of their employees, and they

recognize that many skills are best taught by people other than themselves.

Cheerleader Managers take a hands-off approach, delivering positive feedback and putting employees

in charge of their own development. They are available and supportive, but they

aren’t as proactive as the other types of managers when it comes to developing employees’

skills.

The four types are more or less evenly distributed

within organizations, regardless of industry. The most common type,

Cheerleaders, accounts for 29% of managers, while the least common, Teachers,

accounts for 22%. The revelations in the research relate not to the prevalence

of the various styles but to the impact each has on employee performance.

The first surprise: Whether a manager spends 36% or 9% of her

time on employee development doesn’t seem to matter. "There is very little

correlation between time spent coaching and employee performance,” says Jaime

Roca, one of Gartner’s practice leaders for human resources. "It’s less about

the quantity and more about the quality.”

The second surprise: Those hyper vigilant Always-on

Managers are doing more harm than good. "We thought that category would perform

the best, so this really surprised us,” Roca says. In fact, employees coached

by Always-on Managers performed worse than those coached by the other types—and

were the only category whose performance diminished as a result of coaching.

The researchers identified three main reasons for

Always-on Managers’ negative effect on performance. First, although these

managers believe that more coaching is better, the continual stream of feedback

they offer can be overwhelming and detrimental. (The Gartner team compares them

to so-called helicopter parents, whose close oversight hampers children’s

ability to develop independence.) Second, because they spend less time

assessing what skills employees need to upgrade, they tend to coach on topics

that are less relevant to employees’ real needs. Third, they are so focused on

personally coaching their employees that they often fail to recognize the

limits of their own expertise, so they may try to teach skills they haven’t

sufficiently mastered themselves. "That last one is a killer—the manager

doesn’t actually know the solution to whatever the problem is, and he’s

essentially winging it and providing misguided information,” Roca says.

When the researchers dove deep into the connection

between coaching style and employee performance, they found a clear winner:

Connectors. The employees of these managers are three times as likely as

subordinates of the other types to be high performers.

To understand how Connectors work, consider this

analogy from the world of sports: A professional tennis player’s coach may be

the most important voice guiding the player’s development, but she may bring in

other experts—for strength training, nutrition, and specialized skills such as

serves, lobs, and backhands—instead of trying to teach everything herself.

Despite this outsourcing, the coach remains deeply involved, identifying

expertise, facilitating introductions, and monitoring progress.

Encouraging managers to adopt Connector behaviors

may require a shift in mindset. "Historically, being a manager is about being

directive and telling people what to do,” Roca says. "Being a Connector is more

about asking the right questions, providing tailored feedback, and helping

employees make a connection to a colleague who can help them.” The most

difficult part is often self-knowledge and candor: Being a Connector requires a

manager to recognize that he’s not qualified to teach a certain skill and to

admit that deficiency to a subordinate. "That isn’t something that comes

naturally,” Roca says.

To get started, the researchers say, managers

should focus less on the frequency of their developmental conversations with

employees and more on depth and quality. Do you really understand your employees’

aspirations and the skills needed to develop in that direction? Next, instead

of talking about development only one-on-one, open the conversations up to the

team. Encourage colleagues to coach one another, and point out people who have

specific skills that others could benefit from learning. Then broaden the

scope, encouraging subordinates to connect with colleagues across the

organization who might help them gain skills they can’t learn from teammates.

For employees, one message from this research is

that you’re better off working for a Connector than for one of the other types.

So how can you recognize whether someone is in that category—ideally before

accepting a position? Roca suggests asking your prospective boss about his

coaching style and discreetly talking with his current direct reports about how

he works to upgrade subordinates’ skills.

For managers and subordinates, the research should

redirect attention from the frequency of developmental conversations to the

quality of interactions and the route taken to help employees gain skills. Says

Roca: "The big takeaway is that when it comes to coaching employees, being a

Connector is how you win.”

Source: Harvard Business Review May–June

2018 Issue